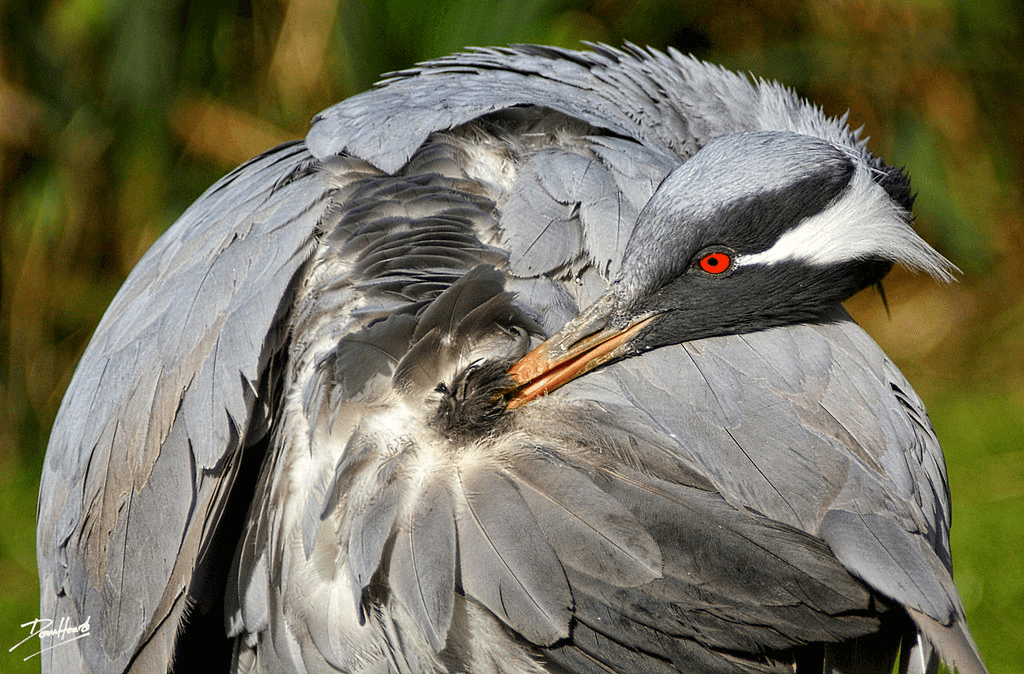

The uropygial gland, also called the preen gland or oil gland, is a bilobed structure on the dorsal base of a bird’s tail between the fourth caudal vertebra and the pygostyle, the structure formed by the fusion of the final caudal vertebrae. The pygostyle is surrounded by flesh, the fleshy structure commonly called the “pope’s nose” by those carving a chicken or turkey. Typically the uropygial gland has a small tuft of feathers that acts a wick for the preen oil. Basically, the uropygial gland produces oils that a bird squeezes from it in order to apply to its feathers, thereby waterproofing them. Uropygial comes from Greek words meaning “rump” and pygostyle from the Greek meaning “rump pillar.”

Clearly, waterproofing feathers is significant, in fact, essential, for most birds but there are nine families of birds that do not possess a uropygial gland. You would think that these would be the non-flying or poor fliers birds: the kiwis (Apterygidae), emu (Dromaiidae), ostriches (Struthionidae), rheas (Rheidae), cassowaries (Casuariidae), mesites (Mesitornithidae), bustards (Otididae) have no preen glands. But neither do pigeons and doves (Columbidae), amazon parrots (Psittacidae), frogmouths (Podargidae), or woodpeckers (Picidae) who keep themselves clean and dry with dust baths.

You would also think that water birds would have well-developed uropygial glands, more so than those of terrestrial birds. Not so. Although there are differences in the size of the uropygial gland with sexes, seasons, habitat, and body weight, no good explanation of the differences has been discovered.

Recent research has indicated that the anti-microbial properties of uropygial oils inhibit the growth of bacterial that degrade feathers. These microorganisms would obviously affect the flight capabilities of birds, affecting their ability to escape predators. It turns out that Goshawks, and probably other similar predators, catch prey that have smaller uropygial glands and presumably less good flyers.

The uropygial gland may also play a role in diminishing predatory pressure by switching chemicals to a less volatile one during nesting season. In other words, when a pair of birds is nesting, the chemicals the glands produce are less likely to be detected by predators. And, in an experiment with starlings, investigators found that the birds could determine the sexes of conspecifics by chemical emitted by the uropygial gland.

Odors have been shown to influence the choice and synchronization of partners, the choice of nest-building material or the care for the eggs and offspring. There has been a lot of research on the odor detection of birds in the past, mainly by measuring the size of the olfactory bulbs. As you might expect, seabirds, which find their food by olfaction, have the largest olfactory bulbs, while songbirds have the smallest. It turns out, however, that the size of the olfactory bulb is only distantly related to its sensitivity to scents.

The information we have now is both vague and minimal. It’s going to take more research to determine how birds smell and how the uropygial gland affect bird physiology and behavior.