The skin covers the body of birds and produces feathers and a variety of other external structures: beak covering, wattles, comb, scales of feet and legs. The skin is thinner than mammals’ and attaches to the skeleton in a number of places: skull, beak, wrist, wing tips, dorsal side of the pelvis, tarsometatarsus, and toes. The general function of the skin is protective, the base of external features, and serves as a large sensory organ with receptors for temperature, pressure, and vibration. One or two glands at the base of the tail (uropygial glands) produce fatty secretions.

Feathers are the one most distinguishing characteristic of birds. For many years it was thought that feathers evolved as an elongation of reptilian scales. It seemed to make sense because reptile scales and bird feathers have some chemical and structural components in common. It was thought that the scales got longer to serve first as insulation as reptiles and their bird descendants were developing homeothermy (homeothermy). But we were wrong on both counts. It appears that bird scales arose anew as novel structures and their purpose was not flight or insulation, but communication as these first feathers were useless for anything, but they were colored, indicating that they were some sort of signal.

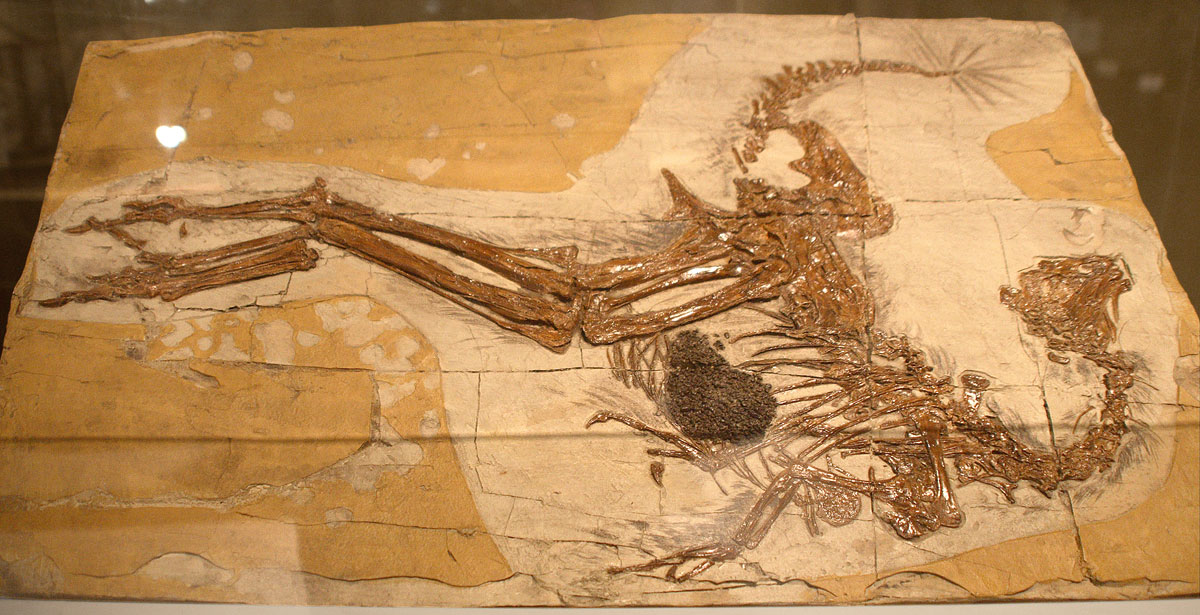

Here’s one of the first dinosaur fossils showing feather impressions.

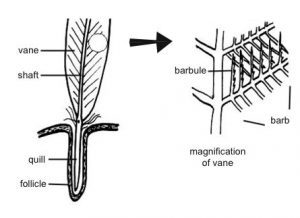

Modified from Wikipedia: There are two basic types of feather: vaned feathers which cover the exterior of the body, and down feathers which are underneath the vaned feathers. The pennaceous feathers are vaned feathers. Also called contour feathers, pennaceous feathers arise from tracts and cover the entire body. A third rarer type of feather, the filoplume, is hairlike and (if present in a bird; they are entirely absent in ratites – large flightless birds) grows along the fluffy down feathers. In some passerines, filoplumes arise exposed beyond the contour feathers on the neck.[1] The remiges, or flight feathers of the wing, and rectrices, the flight feathers of the tail are the most important feathers for flight.  A typical vaned feather features a main shaft, called the rachis. Fused to the rachis are a series of branches, or barbs; the barbs themselves are also branched and form the barbules. These barbules have minute hooks called barbicels for cross-attachment. Down feathers are fluffy because they lack barbicels, so the barbules float free of each other, allowing the down to trap air and provide excellent thermal insulation. At the base of the feather, the rachis expands to form the hollow tubular calamus (or quill) which inserts into a follicle in the skin. The basal part of the calamus is without vanes.

A typical vaned feather features a main shaft, called the rachis. Fused to the rachis are a series of branches, or barbs; the barbs themselves are also branched and form the barbules. These barbules have minute hooks called barbicels for cross-attachment. Down feathers are fluffy because they lack barbicels, so the barbules float free of each other, allowing the down to trap air and provide excellent thermal insulation. At the base of the feather, the rachis expands to form the hollow tubular calamus (or quill) which inserts into a follicle in the skin. The basal part of the calamus is without vanes.

Flight feathers are stiffened so as to work against the air in the downstroke but yield in other directions. It has been observed that the orientation pattern of β-keratin fibers in the feathers of flying birds differs from that in flightless birds: the fibers are better aligned in the middle of the feather and less aligned towards the tips.

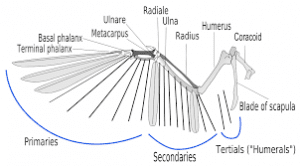

In the wing there are several categories of feathers, classified by their location and function. The outer primary feathers are attached to the hand bones and serve as propulsion mechanisms. The secondary feathers are attached to the ulna and serve mainly to provide lift. The tertial feathers are attached to the humerus and provide some lift but mainly fill the space between the body and the secondary feathers. Overlying the forward part of the main wing feathers are covert feathers, which also cover much of the body. Their purpose is partly insulation and decoration but mainly to streamline the bird’s body for flight.

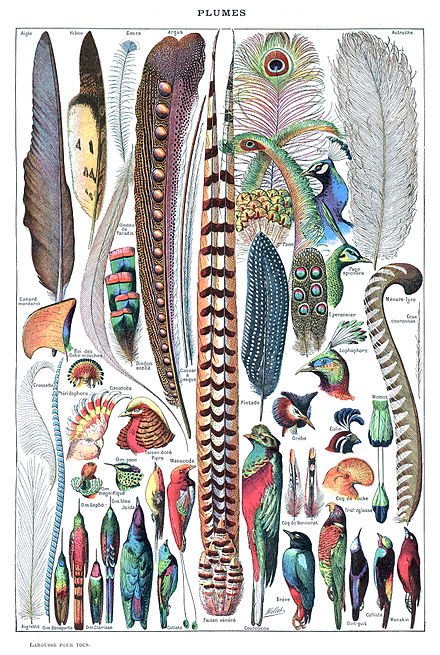

Feathers insulate birds from water and cold temperatures. They may also be plucked to line the nest and provide insulation to the eggs and young. The individual feathers in the wings and tail play important roles in controlling flight. Some species have a crest of feathers on their heads. Although feathers are light, a bird’s plumage weighs two or three times more than its skeleton, since many bones are hollow and contain air sacs. Color patterns serve as camouflage against predators for birds in their habitats, and serve as camouflage for predators looking for a meal. Striking differences in feather patterns and colors are part of the sexual dimorphism of many bird species and are particularly important in selection of mating pairs. In some cases there are differences in the UV reflectivity of feathers across sexes even though no differences in color are noted in the visible range.

All About Birds

All About Feathers

Bird Feathers

EcobirdsEverything You Need to Know About Feathers

Feather Atlas

Feathers

Molecular Feather Evolution

Feathers – Wikipedia

The Feathers Site

The Feather Trade