The term Pfeilstorch (German for “arrow stork”)defined storks pierced by an arrow or spear while wintering in Africa, before returning to Europe with the missle in their bodies. To date, around 25 Pfeilstörche have been documented. The first and most famous Pfeilstorch was a white stork found in 1822 near the German village of Klütz, in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. It was carrying an arrow from central Africa in its neck. The specimen was stuffed and can be seen today in the zoological collection of the University of Rostock. This Pfeilstorch was crucial in understanding the migration of European birds. Before migration was understood, people had no other explanation for the sudden annual disappearance of birds like the white stork and barn swallow. Some theories of the time held that they turned into mice, or hibernated at the bottom of the sea during the winter, or even that birds flew to the moon for the winter. The arrow storks proved that birds migrated long distances to wintering grounds on an annual basis.

For over a century, people have been banding birds (or ringing them as it is called in Europe) to determine their longevity, breeding and wintering areas, and routes of migration. Report Recovery of a Bird with a Metal Leg Band 1-800-327-BAND Or Submit Electronically.

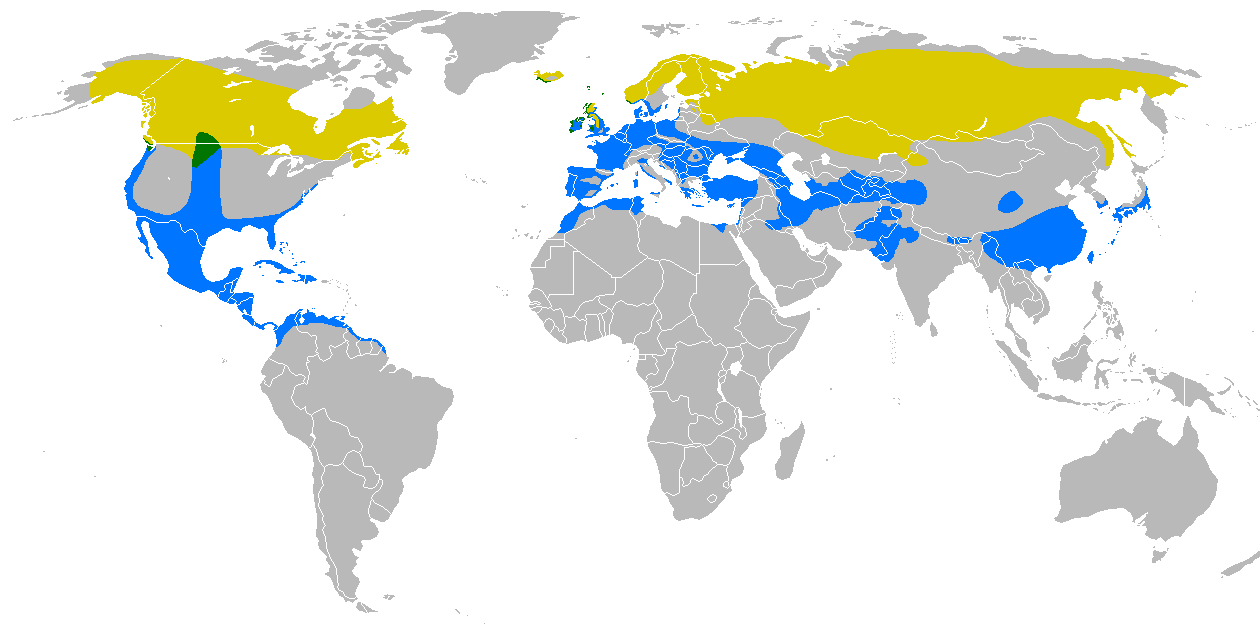

Migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south along a flyway between breeding and wintering grounds. About 40% of bird species migrate. Migration carries high costs in predation and mortality, including from hunting by humans, and is driven primarily by availability of food. It occurs mainly in the northern hemisphere, where birds are funnelled on to specific routes by natural barriers such as the Mediterranean Sea or the Caribbean Sea.

Historically, migration has been recorded as much as 3,000 years ago by Ancient Greek authors including Homer and Aristotle, and in the Book of Job, for species such as storks, turtle doves, and swallows. More recently, Johannes Leche began recording dates of arrivals of spring migrants in Finland in 1749, and scientific studies have used techniques including bird ringing and satellite tracking. Threats to migratory birds have grown with habitat destruction especially of stopover and wintering sites, as well as structures such as power lines and wind farms.

The Arctic tern holds the long-distance migration record for birds, travelling between Arctic breeding grounds and the Antarctic each year. Some species of tu benoses (Procellariiformes) such as albatrosses circle the earth, flying over the southern oceans, while others such as Manx shearwaters migrate 14,000 km (8,700 mi) between their northern breeding grounds and the southern ocean. Shorter migrations are common, including altitudinal migrations on mountains such as the Andes and Himalayas. The Bar-tailed Godwit migrates in flocks to coastal East Asia, Alaska, Australia, Africa, northwestern Europe and New Zealand. It was shown in 2007 to undertake the longest non-stop flight of any bird. Birds in New Zealand were tagged and tracked by satellite to the Yellow Sea in China. According to Dr. Clive Minton (Australasian Wader Studies Group): “The distance between these two locations is 9,575 km (5,950 mi), but the actual track flown by the bird was 11,026 km (6,851 mi). This was the longest known non-stop flight of any bird. The flight took approximately nine days. At least three other bar-tailed godwits also appear to have reached the Yellow Sea after non-stop flights from New Zealand.” One specific female of the flock, flew onward from China to Alaska and stayed there for the breeding season. Then on 29 August 2007 she departed on a non-stop flight from the Avinof Peninsula in western Alaska to the Piako River near Thames, New Zealand, setting a new known flight record of 11,680 km (7,258 mi).

benoses (Procellariiformes) such as albatrosses circle the earth, flying over the southern oceans, while others such as Manx shearwaters migrate 14,000 km (8,700 mi) between their northern breeding grounds and the southern ocean. Shorter migrations are common, including altitudinal migrations on mountains such as the Andes and Himalayas. The Bar-tailed Godwit migrates in flocks to coastal East Asia, Alaska, Australia, Africa, northwestern Europe and New Zealand. It was shown in 2007 to undertake the longest non-stop flight of any bird. Birds in New Zealand were tagged and tracked by satellite to the Yellow Sea in China. According to Dr. Clive Minton (Australasian Wader Studies Group): “The distance between these two locations is 9,575 km (5,950 mi), but the actual track flown by the bird was 11,026 km (6,851 mi). This was the longest known non-stop flight of any bird. The flight took approximately nine days. At least three other bar-tailed godwits also appear to have reached the Yellow Sea after non-stop flights from New Zealand.” One specific female of the flock, flew onward from China to Alaska and stayed there for the breeding season. Then on 29 August 2007 she departed on a non-stop flight from the Avinof Peninsula in western Alaska to the Piako River near Thames, New Zealand, setting a new known flight record of 11,680 km (7,258 mi).

The timing of migration seems to be controlled primarily by changes in day length. Migrating birds navigate using landmarks, celestial cues from the sun and stars, the earth’s magnetic field, and perhaps mental maps. Some apparently use their sense of smell and there is some indication that infrasound may play a role in navigation. But climate change is having an effect on the timing of migration. According to Nature Canada:

- Birds are migrating earlier in the spring. A study of 63 years of data for 96 species of bird migrants in Canada showed that 27 species have altered their arrival dates significantly, with most arriving earlier, in conjunction with warming spring temperatures.

- Birds also seem to be delaying autumn departure: in a study of 13 North American passerines, 6 species were found to delay their departure dates in conjunction with global warming.

- Some birds in Europe are even failing to migrate all together.

- Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas data demonstrates that “southern” birds species such as Tufted Titmouse, Blue-Gray Gnatcatcher, Northern Mockingbird, and Red-bellied Woodpecker have increased in number and have expanded their range northwards in Ontario compared to 20 years ago.

Birding by Radar – many references

Bird Migration

Bird Migration and Navigation

Hawk Migration Association Migratory Bird Day

Migratory Bird Day

Migration of Birds

Migration Watch (GB)

Migration and Climate Change

Mystery of Migration

Nine Awesome Facts About Bird Migration

Operation Migration

Partners in Flight

Radar Ornithology – Clemson University

Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center

Spring and Fall Migration Timetables

The Epic Journeys of Migratory Birds

USFWS Division of Migratory Bird Management

Pingback: Can Birds Predict the Climate? – Ornithology - Specialpets

Pingback: Can Birds Predict the Weather? – Ornithology - NimasPark

Pingback: Can Birds Predict the Climate?- Ornithology - Birds2nest