Excerpted from Beaks, Bones and Bird Songs:

From the Old French fourrage, to forage, pillage, or plunder, foraging refers to the ways birds find food. Virtually every bird has its own style of seeking out and acquiring its sustenance with each beak shape allowing a range of behavior and diet. Since we are most familiar with the birds that visit our feeders, let’s start with the seed eaters. I have watched White-crowned Sparrows gingerly manipulate seeds to husk them, followed by Eurasian Collared Doves which just gulp the larger seeds down and the California Scrub Jay which sweeps through the seeds, scattering many to the ground in order to find the bigger ones. There are wide differences in seed sizes, shapes, and hardness and subsequently extensive variation in bird bill sizes and shapes, but seedeater bills are basically conical. The lower jaws of seed eaters are heavily muscularized, enabling the jaw to push the seed upward into the almost immoveable upper jaw. The hard palate of the upper jaw is heavily keratinized (that structural protein of our fingernails), has ridges, bumps, and spine-like projections that serve to husk the seed. In general, the deeper the bill, the larger the seed that can be handled as bill depth allows more musculature and thus greater forces to be exerted. Finches place the seed laterally on the edge of their lower jaw and move the jaw slightly forward and back to crack it; to husk it, the seed is moved to the middle of the palate and the jaws are moved laterally until the shell comes off. Smaller-billed birds can only handle smaller, softer seeds than larger billed birds which can handle both small and large seeds.

In general, birds will choose the seeds that are most available and easily handled. Watch the dining habits of these birds at your feeder closely and I’m certain you’ll discover lots of different styles, like your relatives at Thanksgiving dinner. Evening Grosbeaks, named by French explorers who thought the birds only fed in the evening, have a large heavy bill which can exert over 125 lbs/in2 , enough to crack open cherry pits. American Robins have been observed devouring the

crop of a cherry tree, swallowing the fruit and regurgitating the seeds which were then feasted on by Evening Grosbeaks. I can personally attest to the strength of a heavy-beaked Northern Cardinal I captured drew blood from my index finger before I could release him. The Red Crossbill is a specialized seed-handler. The crossed mandibles and strong jaws of these birds enables them to pry open the scales of pine cones and extract the small seeds. This gives them almost exclusive access to this seed source, but since extraction takes a lot of time, crossbills need seed abundances 2-3 times greater than non-crossbill species to fill their daily energy requirements. Interestingly, when holding a cone with a foot while extracting a seed, individuals with the lower mandible crossed to the right hold the cone with their right foot, and vice versa. Acorn Woodpeckers of California and the southwest store acorns in “granary” trees and defend them aggressively. They wedge the acorns into holes in trees or wooden telephone poles so tightly that crows, squirrels, or rats can’t raid their supply. When they need an acorn, a woodpecker hammers it with its bill to crack the shell and extract the meat. European Nutcrackers hide nuts and acorns in the soil or in the snow and uncover them later, overlooking some seeds that then may become new trees. Clark’s Nutcrackers cache two to three times what they need for the winter and eventually find only 50% of their seed caches.

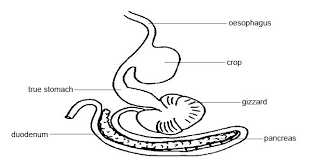

Florida Scrub Jays also cache food by burying one acorn at a time; but if they observe another jay, a potential cache robber, watching them, they will return later to move the acorn. But they will only do this if they themselves were cache robbers in the past. Seems that honest jays trust the other ones and thieves do not. Seeds are not easy to digest, so after the seeds are swallowed they move to the crop, from the Old English cropp, meaning craw, an expanded part of the esophagus. Rather than eating food slowly and digesting it before moving on, birds with a crop fill it to almost bursting. Digestion then begins as the food slowly makes its way downward. Dr. Thomas Caceci, a veterinarian, opened the crop of a one pound pigeon to find a half pound of corn. A Wood Duck he dissected had ten decent sized acorns in its crop; a human would have to swallow ten golf balls to equal that trick. From the crop the food goes down the small intestine to the glandular part of the stomach that secretes digestive enzymes. The second part of the stomach is the ventriculus or gizzard, from the Old French gesier, meaning chicken entrails, is muscular and does the mechanical grinding of food. The gizzard takes the role of teeth in a bird and often contains sand grains or small rocks to help in the process. Some say that if you hold a live chicken up to your ear you can hear the stones grinding in its gizzard.

I am a forestry student from India and I’m am facinated by birds,so I wanted to ask you how do I get to study or have a degree in ornithology

Please go to my page on Ornithology careers at https://ornithology.com/careers/ and it should tell you everything you need to know about careers in ornithology.